LITCHFIELD PARK, Ariz. — Nancy Root remembers when she vanished.

Not the exact date, but the occasion: She went shopping for a mattress. This was a few years ago. Because the mall was so big and her legs were so weak, she used a wheelchair, which was new to her, and had a friend push her.

Their wait for service was unusually long, and later, as she used the wheelchair more and more, she understood why. In the chair she became invisible. In the chair she turned radioactive. People looked over her, around her, through her. They withdrew. It was the craziest thing. She had the same keen mind, the same quick wit. But most new acquaintances didn’t notice, because most no longer bothered to.

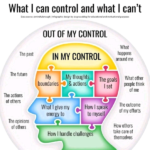

She told me all of this recently not in anger but in bafflement. Could I explain why her infirmity and her age — she’s 82 — erase her? She has her own theories. Maybe strangers worry that she’ll need something from them. Maybe they see in her their worst fears about their own futures.

Probably they extrapolate from her physical diminishment. “They think I’m mentally incapacitated,” she said. “I’m sure of that. I’d stake my life on it.”

“Doctors’ offices are the worst,” she added, describing how receptionists address whoever’s pushing her. “I’m not acknowledged. ‘Does this lady have an appointment?’ ‘Does this lady have her medical card?’ They don’t allow this lady to have a brain.”

But it’s not just receptionists. It’s flight attendants. Movie-theater employees. They make dismissive assumptions about people above a certain age or below a certain level of physical competence. Or they simply edit those people out of the frame.

I met Nancy on a Baltic cruise in September, and I couldn’t edit her out of the frame because she was smack in the middle of it, right in front of me, asking smart questions and making even smarter observations. I was one of five speakers giving lectures to a group of about 60 passengers, including her, who’d signed up for them. She traveled with two younger friends who helped her negotiate the ship’s narrow corridors.

But after chatting extensively with the three of them at an initial cocktail-hour reception in one of the lounges, I didn’t spot them at our group’s subsequent social gatherings there. An email that she sent me the following month solved that mystery. “On our cruise,” she wrote, “I again experienced the uneasiness of people toward us ‘physically challenged’ types. Even among our educated group, people ignored me.” So she parceled out her exposure to them. She and her companions did their own thing.

The more I thought about her experience, the more I realized how widespread it undoubtedly is, and how cruel.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that more than two million Americans use wheelchairs for their daily activities and 6.5 million depend on canes, crutches or walkers.

And the country is getting grayer and grayer. There are roughly 50 million Americans age 65 and older, representing about 15 percent of the population. According to projections, there will be 98 million by 2060, representing nearly 25 percent.

Nancy’s infirmity is unusual and goes back to when she was a 2-year-old in the Pittsburgh area in the late 1930s. She had polio, though her parents, knowing how ostracized children with the virus could be, kept that a secret.

“They destroyed all the evidence,” she said, “and they never told me.” Only many decades after the fact did she figure out the truth, and only in recent years did post-polio syndrome — a condition that afflicts many childhood survivors of the disease — degrade her muscles to a point where she was forced to use a cane, then a wheelchair.

Her health was good for most of her life, as she attended Oberlin College, married, had a daughter and went to work for the National Science Foundation and then the Department of Agriculture, where she was an analyst. Her career, she said, made her as conspicuous in her suburban Washington neighborhood as she is invisible in other settings now. “It was frowned upon,” she told me, noting that most of the other mothers back then stayed home. “But I loved it.”

She and her husband retired to the Phoenix suburb of Litchfield Park, where she now lives alone in their three-bedroom apartment. About five years ago, he felt a twinge on the treadmill and was found to have pancreatic cancer. Three months later, he was dead.

That sped her decline. Her arms grew feebler, her legs wobblier. Her pain intensified. Vanity be damned, she wore one of those pendants to be pressed if she fell. But she once forgot to put it on, tripped and lay on the living-room floor from 9 p.m. to 8 a.m., when a housekeeper happened to arrive. She recounted the episode to me in a tone of wonder at life’s freaky occurrences and at our ability to get through them. There wasn’t a scintilla of self-pity in her voice.

She considers herself lucky because her daughter is nearby. She has all the money that she needs. “I have my mind,” she said, “and I see where others are losing theirs.” She reads for many hours every day.

Books were a big topic for us when I visited her a few weeks ago. It frustrates her that she has never finished “Ulysses” or “Finnegans Wake.” We talked about politics, too. About Singapore, where she traveled — with a wheelchair and helpers — about two years ago. About her job with the Agriculture Department and how ethical and underappreciated she always found farmers to be.

Two nights in a row we went out for Italian food, and she insisted on using her cane instead of her chair. She can do that if she takes a Percocet just beforehand and reconciles herself to a snail’s pace. Toward the end of the second night, after two glasses of wine apiece, we mulled the vocabulary of her lot. I confessed that I cringed whenever she called herself “crippled,” which she does, because she values directness and has a streak of mischief in her.

“Well, ‘handicapped’ isn’t supposed to be O.K., and I’m not going to call myself ‘differently abled,’ ” she said. “You’re a writer. Give me a word.”

“What about ‘limited’?” I said. “We’re all limited in ways. You’re limited in a particular way.”

I noticed that our server would stand closer to me than to Nancy and was more voluble with me, even though she could see, if she looked, how vibrant Nancy was.

Nancy increasingly makes peace with such neglect but told me that an elderly, infirm friend of hers has another approach. “She tells people to go to hell,” Nancy said. “I need to take a course from her.”

I don’t know about that. But the rest of us have a lot to learn.