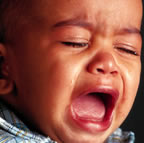

As children we grieve when we have to give up what we have made our own, be it a toy, a tricycle, a best friend or a teacher. There is the sudden upsurge of emotion over the loss, followed by a tearful wail, and then the ritual trot to find a loved one to help us resolve our pain.

As children we grieve when we have to give up what we have made our own, be it a toy, a tricycle, a best friend or a teacher. There is the sudden upsurge of emotion over the loss, followed by a tearful wail, and then the ritual trot to find a loved one to help us resolve our pain.

With age, our losses become more significant, our practice more rigorous, and final resolution more difficult. To meet our needs, societies historically provided an honored space for us to practice our emotional skills.

Grieving rituals, however, are disappearing in favor of ceremonies of celebration. Our current remote control mentality is often intolerant of sorrow and finds little redeeming value in grief. The new paradigm of indifference coincides with the geographical separation of family members, the 3-day family employment leave and the ever-growing influence of the pharmaceutical conglomerates.

“Get over it” has become our contemporary mantra. Can’t snap back? Take a pill.

Why practice sorrow anyway? What possibly could be learned from a long string of opportunity to experience sorrow over the loss of someone or something we treasure? Possibly an increased capacity for compassion. Or the awareness that we are stronger than we assumed. Yes, surely. But maybe there is an even more important reason for practicing grief and learning how to develop and maintain one’s emotional grip.

Inevitably the practice of coping with deep despair allows us to gracefully accept and embrace our most significant and ultimate loss: our own life.