On Being this week features Pauline Boss, professor emeritus at the University of Minnesota. She is the author of Loss, Trauma, and Resilience: Therapeutic Work with Ambiguous Loss, Loving Someone Who Has Dementia, and Ambiguous Loss.

You can read the transcript or listen to Krista Tippett and Pauline on the podcast. I urge you to do one or the other. It will help you better understand yourself, and when isn’t that a good thing?

On Being: The Myth of Closure

There is no such thing as closure. In fact, Pauline Boss says, the idea of closure leads us astray. It’s a myth we need to put aside, like the idea we’ve accepted that grief has five linear stages and we come out the other side done with it. She coined the term “ambiguous loss,” creating a new field in family therapy and psychology. She has wisdom for the complicated griefs and losses in all of our lives and for how we best approach the losses of others.

Excerpt of beginning of interview:

MS. TIPPETT: Here’s a line I found in your writing. I would say this is also a description of spiritual background and, I think, a bridge to the work you’ve ended up doing. You said, “Homesickness was an essential part of my family’s culture.”

MS. BOSS: It was. I think it may be true for all immigrant families, but it certainly was for mine. And it was even in the village because there were many immigrant families there. So it became a sort of pathos that would be in the family when we weren’t even aware of it, except that I could see the sadness periodically, like when my father would get a letter from Switzerland, or worse yet, a letter with a black rim around it, which meant announcement of death in the family. So I was always aware that there was another family somewhere and that there was some homesickness. Except, where was home? I figured that home was in Wisconsin where we lived. Yet I knew he had this other family across the Atlantic that he pined for. My maternal grandmother was the same. Of course, she refused to learn English. She said she lost her mountains, she lost her mother, she lost her friends, and she wasn’t going to lose her language. So I think that, too, is not unusual for immigrant families today, especially the elders.

MS. TIPPETT: One thing reading that about your family made me reflect on is that we talk a lot about immigrants, right? Especially now. We even talk about things like people sending money back to family. But we don’t kind of acknowledge the grief or that homesickness or that sadness, that loss that must always be there, even when people have made a choice to go far away.

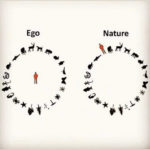

MS. BOSS: I think that’s part of our American culture that we don’t want to hear that. We don’t just deny death in our culture; I think we deny ambiguous loss that comes with things like immigration. Homesickness comes along with that, and we really want people to get over it. And they don’t. In fact, it’s paradoxical. The more you want people to get over it, the longer it will take for them. And why not remember your former country, your former island, your former culture while you’re learning to fit into the new one? In other words, having two cultures is what it ends up being. You have one foot in the old, and one foot in the new. One can live that way. That may be the most honest way to do it.

MS. TIPPETT: What’s interesting to me is the way you started thinking about ambiguous loss. You started with this idea of father absence. You would eventually call this kind “type-two ambiguous loss,” which is, somebody’s here, but they’re not here. We’ll talk some more about these different forms of ambiguous loss and especially this one.

The type-one ambiguous loss that eventually became the other kind of foundation of the field is — I also very much like the stuff on news headlines — so there’s this type of ambiguous loss, which is physical presence and psychological absence, which would also be dementia or mental illness where people incrementally disappear. But there’s also physical absence and psychological presence. So, the person disappears. For me to think about you coining this term in the 1970s and thinking about the MIAs of the Vietnam War — missing in action. I remember growing up in those years. We all wore these bracelets, right, or you had the name of someone? And I think, as a child, being aware of how completely traumatizing that was but probably not understanding that trauma — it’s in these kinds of great disasters where you’ve been called in to help people — with the Red Cross, like that tsunami where people get swept away.

MS. BOSS: I didn’t intend that.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. You mean when you started out?

MS. BOSS: Not at all. I’m not a first responder. I’m not even brave, and I’m not good in the field. But when I was studying this psychological absence, and I gave my first paper on that as a graduate student, the military was in the audience, and they said, “If you would reverse this and study physical absence, we would have data for you on the families of the missing in action soldiers in Vietnam.”

MS. TIPPETT: They had experienced that trauma of people not being able to say goodbye, not being able to bury their dead.

MS. BOSS: Yes. And it was the military from The Center for Prisoner of War Studies in San Diego who recognized that. They said I had a theory, and they had data, and could we get together? I was going to write my dissertation on psychological father absence, so that got dropped. Instead, I wrote it on physical father absence, because at that time, the MIAs were all male. That took me down this road of more disastrous kinds of losses outside the home, and the rest is history.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. [laughs] And maybe it’s just because I’ve been aware of your work and in this on and off conversation with you. I feel like these kinds of events are just that much more in our cultural imagination.

MS. BOSS: They are.

MS. TIPPETT: The Malaysian airplane that disappears without a trace — maybe it’s also because the cameras are ever-present, and we see that these people, these family members, cannot find peace.

MS. BOSS: I think it’s personal too. You’re absolutely right that you can’t pick up the newspaper without — I think almost each day — finding some kind of missing person or disappearance or someone regarding some kind of physical loss each day. But I think it also hits our psyche deeply. We come from culture in this country of, I think, mastery orientation. We like to solve problems. We’re not comfortable with unanswered questions, and this is full of unanswered questions. These are losses that are minus facts. Somebody’s gone. You don’t know where they are. You don’t know if they’re alive or dead. You don’t know if they’re coming back. That kind of mystery, I think, gives us a feeling of helplessness that we’re very uncomfortable with as a society. So I think we’re taken to this idea that we see in the paper all the time. It’s not always called “ambiguous loss,” but I think those ideas pull people in because of the helplessness of it, so we say, “Thank God it’s not me.”