What I Can Control and What I Can’t

by Eric Barker

A lot of men were dying and nobody knew why.

In the late 70’s, the CDC realized that a shocking number of Hmong immigrants, ages 25-45, were dying in their sleep. They would gasp for breath but before help could arrive, they were gone. Autopsies revealed nothing. Perplexed, epidemiologists started calling it “Sudden Unexpected Nocturnal Death Syndrome.” SUNDS was killing more Hmong men than the top five causes of death combined.

But someone had an idea. Oddly enough, she wasn’t a doctor; she was an anthropologist. Shelley Adler knew that in Hmong folklore it was believed that the “dab tsog” – an evil demon – could paralyze and smother victims at night. In their home country of Laos, shamans would perform magic to fight off the spirit. But here in the US, shamans were few and far between. And most Hmong no longer practiced the religion they had been raised with.

Enter “Sleep Paralysis.” A very real but usually innocuous medical condition that 8% of people experience. For most of your sleep cycle, your body “switches off” movement. In Sleep Paralysis, your body delays switching it back on. Briefly, you’re conscious — but unable to move. Very scary though harmless. But Shelley thought the men were interpreting this as the dab tsog attacking them. They’d panic and some would have a heart attack. And as word spread about the deaths, more and more Hmong men became afraid, and thereby susceptible.

Shelley turned out to be right. However, Western medicine wasn’t very effective in getting the Hmong to give up the ideas they’d been raised with. And the deaths continued…

Again I am featuring German therapist Nik Golke’s latest blog post because he understands the power of using story to make his point. In working with hundreds of people suffering personal loss at hospice and in my private practice, the “good-sad” is so often the other side of the grief coin. It comes when we realize the thought of the loss no longer wounds. Have a good week. Sending love, Vicki

The first time we stand at the grave of someone we loved, we might cry our eyes out. The hundredth time we visit them will look very different.

We may stand in silence, quietly smiling at the thought of what their presence felt like. We may dig through our fondest memories, shaking our head in disbelief that they actually pulled off this one thing. We may even have a lively chat about what happened at work that week. “You should have seen me, Mel. You’d have laughed yourself silly!”

This is the good kind of sad. It’s not the sadness we’re most familiar with, but it’s important to remember it exists. Sadness is not a universally negative emotion. Over time, it can transform. What feels sad-sad now might one day feel good-sad.

There’s a How I Met Your Mother episode in which Marshall holds a BBQ next to his father’s tombstone in order to continue their New Year’s Day tailgating tradition. At first, Marshall is all alone, enjoying some quiet conversation with the ghost of his dad, but then, more and more people show up. “Can I get a hamburger?” “Do you have any more beers?” “Would you mind passing the chips?” Before he knows it, Marshall is hosting a full-on “grillfest,” as we call it in Germany. For a second, he gets annoyed at all the visitors intruding on his space, but then he remembers: Tailgating with his dad was always a party. “The more the merrier,” he’d say — and so does Marshall, handing over the pickles. The good kind of sad.

In The Comfort Book, Matt Haig describes it as “a gentle sadness that almost feels good.” It could be nostalgia or a dream that almost came true. Good-sad is life’s way of reminding us that it is “capable of such warm things,” and that, astonishingly, “we were there to witness them.”

Below is an excerpt from Human Stuff by Lisa Olivera’s latest blog post. I loved it! And I think you will too.

My arms are around you all, readers!

Have a good week.

Love, Vicki

(Excerpt)

If being the best, being unique, and being ranked as superior are the only things that make creating worth our time, we’re putting ourselves in quite a bleak bind, because those things often won’t be the case. Yet when we choose to show up for our work, our art, our callings, our passions, our creations, and our gifts anyway, we put more goodness in the world. We put more beauty in the world. We put more meaning in the world. We put more connection in the world. We put more hope in the world. We put more humanity in the world. And that matters, whether or not it’s one of a kind. That matters, whether or not it’s the best. That matters, whether or not it fits into some hierarchy we never even opted into.

We’ve been so conditioned to view what we do in comparison to others, to rank it and place it into a better or worse category, to find its value not in how it makes us and others feel, but in how individually unique and superior it is. We’ve been conditioned to think there’s only room for a select few so we must be the best — to see others as competition instead of companions — to dismiss our gifts if they don’t meet some externally-based standard — to view outcome as more important than the process of creating itself. We’ve been conditioned to think in terms of productivity and winning, of constant growth and surpassing, of individual success and social status. It’s no wonder we constantly question what we’re creating, sharing, and doing.

James Clear says:

Whatever age you are today, your future self would love to be it.

Most people do not consider 65 to be a young age… but when you’re 75, you’d love to rewind to 65 and regain those years. Few people would describe 35 as your youth, but in your mid-50s your mid-30s will seem like the “young you.”

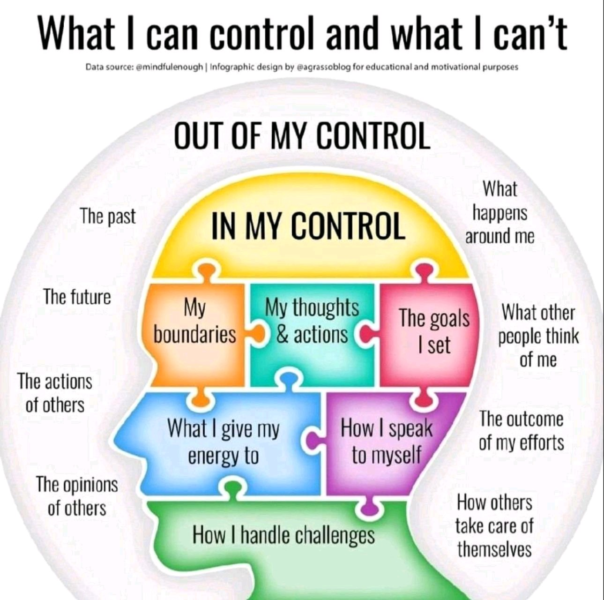

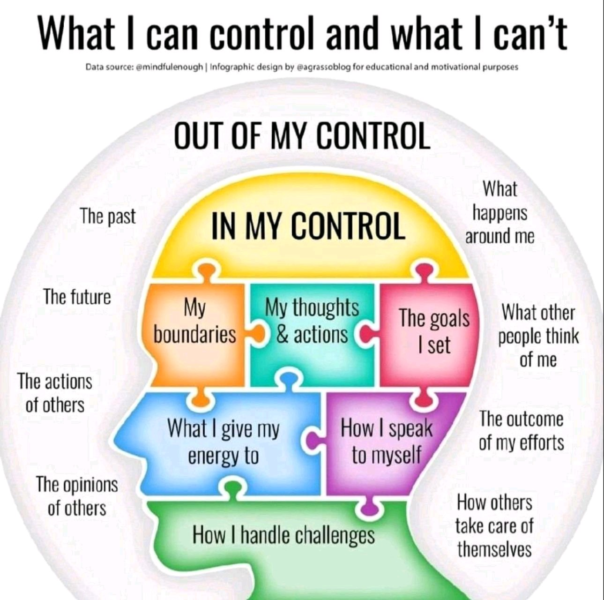

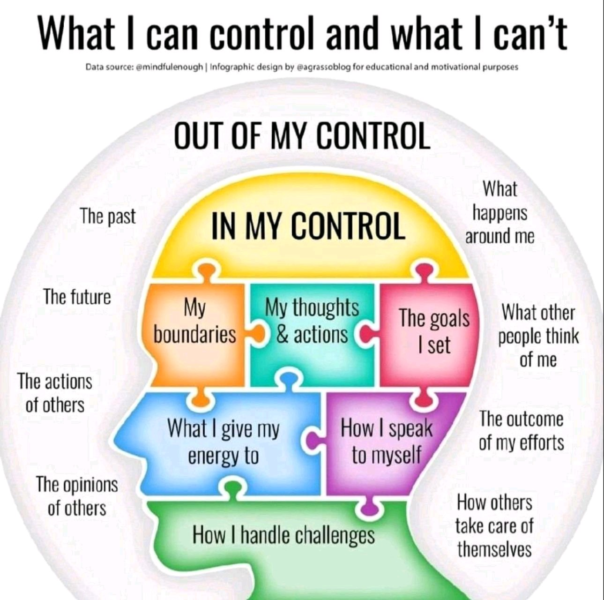

We can all get into the trap of feeling swamped by real and imagined problems, vs. taking what is evident and solving the issue at hand.

The Buddhist perspective would be to surrender to what is in front of you, do what you can, and then get on with your life. And to do that well–one has to possess a healthy dose of acceptance.

Below is short excerpt on topic from Golke’s recent blog.

by Nik Golke

The problem with problems is that you can solve only one at a time. Once you go into the realm of real-time and energy, there’s only so much you can spend on any given issue before you run out of steam, another becomes more important, or it escalates to the point of rendering the solution moot.

Below is what Maria Popova (of The Marginalian fame) posted on her Unselfing Social webpage:

“Somewhere along the way, in the century of the self, we forgot each other. We forgot this vast and wonder-filled universe, of which we are each but a tiny and transient wonder.

Copyright © 2013-14 TalkingGrief.com | A Property of Comfort Care Connection