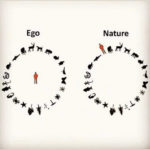

If there’s one error of thought that most reliably holds me back from living an absorbing and meaningfully productive life, it’s the idea that certain things really matter, when the truth is that they don’t matter at all. Or at least nowhere near as much as I seem to believe.

A deliberately mundane example: on Saturdays, I take my son to a kickboxing class where attendees don a special uniform, recite a pledge to use their powers only for good, then spend a surprisingly large proportion of the rest of the hour playing The Floor is Lava. The venue is some distance away, and the class starts early – so if we want to be on time, it’s important to stay on schedule. All too easily, and especially if we’re running late, I’ll slide into an edgy mindset – it’s more of a bodily state, really, complete with tightened jaw and maybe a knot in my stomach – that seems to express the conviction that it would be terrible if we were late. I grow irritable, and thereby make life a little less enjoyable for me and my son. Yet the truth is that, while it’s important to stay on schedule if you want to get to kickboxing on time, what’s not remotely important is getting to kickboxing on time. It just doesn’t really matter.

Timings and schedules seem especially fraught for me in this regard. Before an early flight, I’m prone to waking throughout the night, seemingly subconsciously terrified of missing it, even though I could afford to buy a new ticket if I had to. (True, I couldn’t afford to do so over and over again – but since this has never come to pass even once, that’s a bridge I’ll cross if I ever get to it.) It also often arises, for me and for others, in a horror of failing to meet obligations, or of letting people down, even though, as Laura Vanderkam writes somewhere, the single most likely consequence of your backing out of a commitment you’d made to someone else is… well, nothing.

It’s as if we confuse the conditional kind of importance – that if you want result X, you’d better take action Y – with the unconditional kind, ie., that it would be absolutely terrible if result X didn’t come to pass. There are certain situations where it really would be terrible. But there are vastly more occasions when it wouldn’t be.

At this point, my inner critic anticipates a barrage of objections: “Being punctual shows respect, and sets a good example to your son!” “Only a very privileged person could write what you wrote about purchasing a new plane ticket!” “Some people would get fired or starve if they neglected their obligations as you suggest!” There’s truth in all of these, and they help bring into focus what I really want to say, which isn’t that anybody can, or should, sail through life without a care. Rather, it’s that for some of us, the default approach is to go through the day implicitly treating all sorts of things as matters of life and death when they aren’t even close to being matters of life and death.

I say “implicitly” because intellectually, of course, I know it doesn’t matter if we’re late for kickboxing. It’s just that you’d never know this from the way my muscles clench, or from the tug of urgency that takes up residence in my stomach.

It’s not my purpose today to unpick the reasons for this (although when scouring your childhood or family history for answers, it’s always worth recalling the haunting words of the psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott: “The catastrophe you fear will happen has already happened”). Nor do I come bearing any nifty techniques for eliminating the tendency once and for all. But I’ve found it extremely useful simply to see what’s going on here – and then, at least sometimes, when I find myself slipping into the mindset I’ve been describing, to be able to ask myself: “Wait. Does this actually matter?”

It’s amazing how often the answer is a forehead-slappingly obvious no. Whereupon my shoulders drop, and I exhale, and at least for a few moments, I get to experience what I believe Jiddu Krishnamurti was talking about when he described the secret of his serenity: “I don’t mind what happens.”

I’m no Krishnamurti. In plenty of situations, I do mind what happens, and perhaps quite rightly as well. But much of the time, my “minding” is more just a sort of bodily habit – an unreflecting assumption that if I’m faced with a task or a decision, I should proceed on the basis that it’s really important that things turn out right. And that’s a habit I can drop as soon as I’m aware of it. Whereupon I get to inhabit the present moment more fully and enjoyably, instead of always anxiously waiting to see if things turn out the way I’ve decided they must. Plus, I get to do stuff more freely – to make decisions and take action and accomplish things, instead of holding back out of the fear that things might go catastrophically wrong.

And so, once more, I get to experience the remarkable upsides of the inner shift, both bodily and psychological, that could be summed up in a single instruction: “Unclench.”