(Excerpt from coming book, Help! Someone Died!)

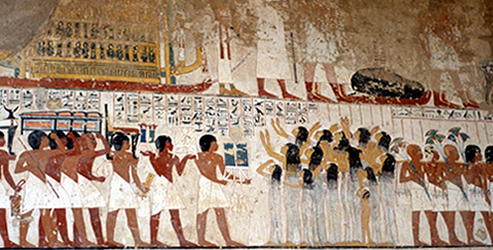

Ancient Egypt: Tomb of Ramos – Funeral Procession

Evidence of the desire to reunite a decedent’s soul with their ancestors in the spirit world goes back to Neanderthal man. This ceremonial quest for immortality continued, for the most part, to be the norm up to and into our contemporary western funerals. *

Until the 1960’s.

The 1960’s Revolution

The 60’s brought revolutionary change to every facet of society as young people disrupted and deconstructed the socio/political process and pulled away from organized religion.

Today, our American culture continues to shift from the sacred to a secular end-of-life service, except for active Catholics, High Episcopalians, Muslims and members of the Orthodox faiths.

The ever-evolving end-of-life practices

- Obituaries: In the past a short obituary ran in the local newspaper giving the deceased’s name, date and cause of death, and time and place for the visitation and funeral service. Now, if an obituary is published in a local paper or online, the primary focus in on the deceased’s life. The cause of death is often omitted, and service details may or may not be listed.

- Visitation: In the past, one or two evenings were set aside prior to the funeral so friends could gather at the funeral home and view the deceased in an open casket. (The exception: Jewish tradition required burial within 24 hours of death.) Now visitations are less common because younger generations consider an open casket barbaric.

- Caskets: Traditionally the casket was present at the funeral. Seldom are caskets present at memorial and Celebration of Life services.

- Cremation: Embalming of the body and in-ground burial is losing favor to cremation. The funeral industry projects that 60% of the deceased in US will be cremated by 2025. The deceased’s ashes are typically 1) kept in the home in a decorative urn, 2) buried at the local cemetery, or in the yard at the family residence, 3) scattered at land, sea or from the air, or 4) placed in a columbary (a separate cemetery building set aside for cremated remains).

- Creative services

- Services are often delayed, so out-of-town family and friends have more time to make travel arrangements.

- Many families schedule a private family-only burial before or after the service.

- Some an end-of-life services are by invitation only.

- Family members plan the memorial service or Celebration of Life from beginning to the end, often eliminating clergy and the funeral director entirely.

- Instead of focusing on life after death, the new services focus on the living memories of the deceased. Instead of being scheduled at a religious venue, they are held in afuneral home, a mausoleum (if it is a crypt service), or a place that had a special meaning for the deceased.

- Technology enables the family to create and post a video of the service online for those who were unable to attend.

- Since Celebrations of Life and memorial service are more upbeat than funerals, parents feel comfortable including their children.

- Green Burial: Natural or “green” burial isbecoming more common because it saves on cost, uses non-toxic materials, conserves resources used in cremation and has minimal impact on environment. Many funeral homes are certified to guide families through the process.A natural burial means the body is placed in a simple biodegradable coffin or wrapped in a shroud and buried shallow enough for microbial activity to take place. The burial be on private land if it complies with local, county and state regulations. (Often local planning departments request a plat map showing the grave site.) A surprising number of green cemeteries are available throughout the US and listed online at www.naturalend.com/where-to-go.

A major exception: When it comes to death, America is not a melting pot

The evolving end-of-life ritual practice outlined above applies to families who have been on American soil for generations. If the deceased is foreign born or a first generation American, the service is likely to follow the decedent’s traditional cultural practice. Even if younger family members are influenced by American behavior, perspectives on birth, death and grief aren’t easily abandoned.

Unfortunately, we Americans sometimes lack the ability to appreciate and enjoy cultural practices other than our own.

Ata and Morrison** note that “if a foreign-born individual consults a western psychiatrist they could… be confronted by the belief that (their) culturally sanctioned… overt coping strategies and expressions of grief… are pathological.”

Sadly, we can convince ourselves that “if you don’t act like us, there is something wrong with you.”

If you are attending an end-of-life service for someone of another culture, approach the service with curiosity and an open heart. Feel free to call the funeral home or religious venue for information. A representative will gladly explain what you can expect and what, if anything, is expected of you.

* For more information regarding Judaism’s evolving history around afterlife, go online to UC Riverside’s Immortality Project, The cultural and historical development and decline of immortality in Judaism. http://www.sptimmortalityproject.com/background/the-cultural-and-historical-development-and-decline-of-immortality-in-judaism/

** Ata, A and Morrison, G (2005). Health care providers, bereavement anxieties and ethnocentric pedagogy: Toward a sense of otherness. AeJAMH, 4(3).

Subscribe to Blog